In Tasmania in the 1950s in the then small and unhappy place called Georgetown near the mouth of the Tamar River, I lived with my family and attended the local primary school.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

$0/

(min cost $0)

or signup to continue reading

From Grade Three I walked seven blocks to school and after school a group of us, weather permitting, walked out to Low Head (Lagoon beach) or the Surf Beach. We were unsupervised and I couldn't swim so I don't know what anyone was thinking (they weren't ... children were meant to stay outside and come home at dinner time). As none of us died life was an adventure.

The common place to play was in an area above the sand dunes at the surf beach in a very large flat hollow filled with shells and stuff.

The "stuff" was sometimes half a metre thick and crunched underfoot. We spent many hours there, chucking the "stuff" at each other and into the water. No one wondered how all this stuff got there, who might have been there before us, what purpose it might have had or whether it belonged to anyone. Clearly in our little British trained brains it didn't belong to anyone ... not a fence or keep out notice anywhere.

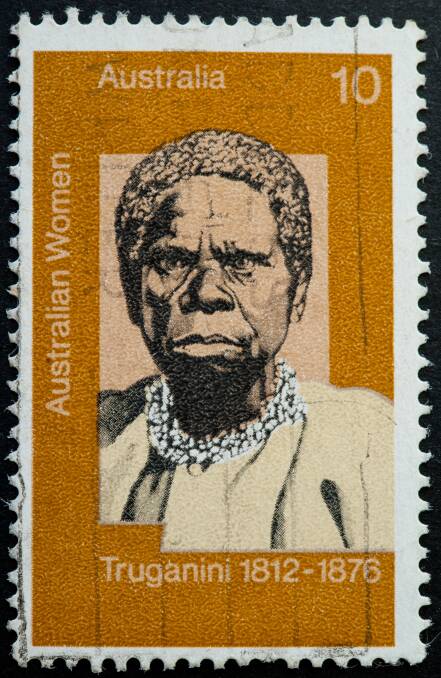

Later when I heard about Truganini, the last Aboriginal to die in Tasmania we were told, I realised that whoever she was and whoever her relatives might have been, they might have lived at our beach and all that "stuff" we played with might have "belonged" to them. It would have been a great camping spot.

I recall feeling awfully uneasy about Trugunini. What did being the "last" Aboriginal mean? The question loomed a bit larger for me because my father had arrived in Australia because Hitler was annihilating Jews. But isn't this what had happened to the Aboriginals? I knew nothing more as far as I can remember about Aboriginals other than they lived in Mia-Mias and had very thin legs like me.

In high school I saw my first black skinned person. I think he was a minister ... someone "important". He stood on the raised platform that teachers used in those days and I sat in the front row looking up at this person in admiration and fear. He didn't make any sense to me because he looked like us but was not us so what could I make of that.

I can't remember what he said but I do remember his voice, his bearing, his masculinity and presence ... impressive, beyond any white bloke I'd ever seen including any swarthy migrant dad I knew. His image remained with me and, as I got older and saw photos of our First People living in humpies, staggering around drunk, kids with snotty noses and skinny dogs I did not see a connection to the memory of this man.

Later still I came across a book of photographs showing strong, healthy, powerful and very healthy Aboriginal people and my memory of that early visitor came alive. I realised then that whatever my views, I was living a life blinded by white settlement history in Australia and the white Christmas experience of the British. The gap was enormous and both those parameters seemed ridiculous.

Flies and incredible heat made a mockery of snowy Christmas trees. And the state of Aboriginal people showed quite clearly that whatever their experiences were, they were way outside my understanding. So this is my take on all this.

Whatever white settlers and administrators genuinely may have believed, they were wrong. They lashed out in fear at what they couldn't understand and remained mired in ideas that led to massive destruction of our First Peoples lives, cultures, family, everything.

And what we have done is try and clean up the mess that has been made without proper consideration of intergenerational trauma, ownership and the sound of their voices. We have said sorry and I am sure most Australians are sorry. We have dished out lots off money and quite a few "white culture" solutions which haven't worked all that well. When they say what they would like they seem to be dismissed.

I found Prime Minister Scott Morrison's comments recently about how he didn't want to appear to encourage racial differences in our multi cultural society absolutely appalling. None of this has to do with race ... we are all Australians and they were here first.

They should be honoured and their stories heard without fear or favour.